The Congo: A Gentle Introduction | Peter Banks

Rwanda is threatening the rotten Congolese state. Open conflict has replaced the chaos of Kinshasan rule. True peace requires a competent state; I will not shed crocodile tears if Kagame brings it

On January 27th, M23 rebels captured the North Kivu provincial capital of Goma. It appears as if Rwanda is on the march again with objectives that are, probably, being written with the ebb and flow of battle. I wanted to try and explain the situation to someone with very little context about Central Africa. This will be an extremely high-level overview of a very complicated situation from the perspective of an American. If you want to know more about the history of the Belgian Congo, I would recommend King Leopold's Ghost by Hochschild—although his facts are debated. For a general history of Africa with great sections on both post-colonial Congo and the Rwandan genocide, read The State of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence by Martin Meredith. But more than any history book, I would recommend reading Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe and Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad. Literature allows you to inhabit a moment more totally than any amount of historical analysis can.

This essay is structured as follows. First, I’m going to give a basic outline of the history of Central Africa up to independence. Second, I’m going to talk about the post-colonial period and the origins of this conflict. Finally, I’m going to explain what is going on today and touch on some thoughts, looking in on this war as an American—especially in light of our shifting self-conception.

That is a pretty big plate1, so let’s lock in. Before I get into the long version, let me do a short version.

Short Version:

After the end of the Rwandan genocide, many of the perpetrators escaped into the eastern Congo. Since Paul Kagame came into power by leading an army of refugee Tutsis back into Rwanda, the entire state was terrified of the Hutu power groups doing the same from their armed camps in the Congo.

In 1997 Kagame and a coalition of allies overthrew Mobutu Sese Seko’s dictatorship over the Congo after he sided with Hutu refugees in their violence against local Tutsis’ in the Congo.

The man who was put into power, Kabila, proved to be simultaneously hostile to foreign (notably Rwandan) meddling in the Congo and unable/unwilling to truly exterminate Hutu power groups. As a result, in 1998 Uganda and Rwanda reinvaded, but rather than the Congolese state collapsing as it had previously, the war became an absolute clusterfuck of foreign interventions that left us with the post-apocalyptic hell environment that defines the modern Congo.

In 2013 a Tutsi (Rwandan)-dominated militia named M23 launched a rebellion against the Congolese state and captured the city of Goma—a city that directly borders Rwanda—defeated some disorganized Congolese counterattacks, and then “disbanded” after international pressure on the Rwandan government intensified.

Well, it appears that Kagame thinks he can test the structure of the Congolese state for a 4th time, and who knows how this will end. If you want to hear his, frankly boring and brazen, thoughts on the matter, watch his speech at the eastern African community here. The fact of the matter is this. The Congo has never operated as a functioning state since its creation in the late 19th century. Yet its borders, which represent the machinations of a Belgian king who had died long before WW1, are treated like a sacral object within whose bounds whoever occupies the city of Kinshasa should be allowed to rape and pillage at their discretion. The legitimacy of the central government is so low that Kinshasa has been forced to turn to a small army of Eastern European mercenaries—a large number of which were captured and marched into Rwanda after Goma fell. This reliance on White mercenaries to maintain centralized control is a common feature of African conflicts from Sierra Leone to the CAR.

It is a fact that North Kivu comes from the same cultural space as Rwanda and shares nothing but a history of Belgian colonial rule with Kinshasa—something it also shares with Rwanda. It is also a fact that if Goma was made to resemble Kigali, it would do more to diminish human suffering than any amount of aid money or education.

The last 70 years of post-War peace, the Pax Americana, has brought about the single most transformational period of economic growth in human history. But it has also been riddled, like all periods, with enormous contradictions. Tyranny comes in many forms, and in Africa, too often the state is more an agent of chaos than order. When you look at the world map or the assembled world leaders in their pressed charcoal suits, it can give the impression that these countries all actually exist. But often they are mere phantasms2.

In reality, there is what I like to call the hierarchy of the state:

If you are at war, you should bring peace—either through victory or surrender.

If you are at peace, you should bring order.

If you have order, you should bring law.

If you have law, you should bring freedom.

For too long, American foreign policy has tried to work backward: by first bringing freedom to a warzone and then watching as an artillery shell violates an entire village’s due process.

Long Version:

“Let there be light”—God”

Central Africa (?–1884):

Central Africa is broadly defined by a couple of geographic and climatic facts. First, in the center of it is a large, basically impenetrable jungle, and second, along the eastern shore, there is an elevated upland, which allows for increased habitability in tropical climates.

In addition, one of the largest rivers in the entire world flows through the impenetrable jungle, almost connecting Africa east to west, and importantly going to the resource-rich province of Katanga. However, the Congo is not a kind river; it is only navigable for certain stretches, and in order to make full use of it, you need an elaborate infrastructure system.

The history of Central Africa “begins” with the explosion of Bantu-speaking farmers out of, probably, what is now Nigeria and Cameroon, southwards into the jungles of Central Africa. As always, when dealing with the history of a group prior to the invention—or more usually transmission—of writing, the exact dates are difficult to know. But the most probable estimates put a first expansion around 3,000 years ago, followed by a second expansion of iron working around the 3rd century BC. Given the absence of an indigenous writings and the general lack of large ruins, it is difficult to know exactly what was going on during or after the Bantu expansion other than what we can glean from linguistic and genetic evidence. What we know for sure are a couple of facts. One, Central Africa was inhabited by people already—in this case hunter-gatherers whose surviving descendants are the modern-day African Pygmies and Khoisan people of southern Africa. Two, Bantu farmers replaced these people through the standard process of genocide and assimilation. And three, by the time Europeans and Muslims began to show up on the scene, this process had long ago been completed—with the exception of South Africa—and the broad linguistic map of Africa was about what it remains today.

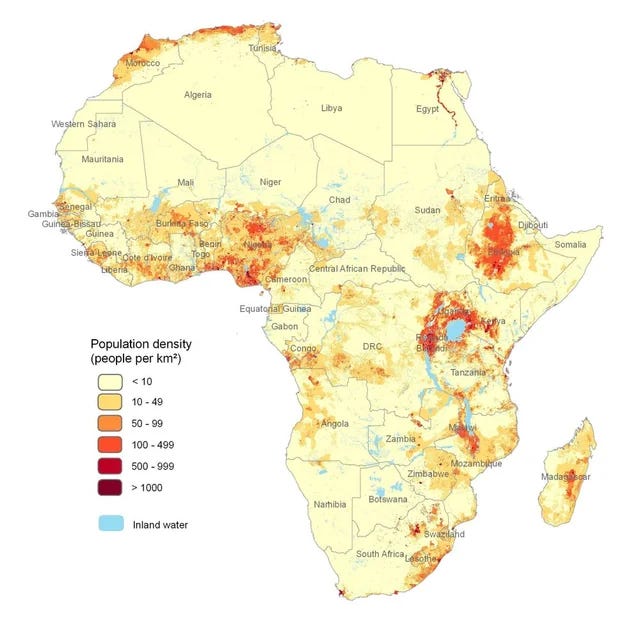

Bantu Central Africa is divided into two broad cultural zones. One near the modern city of Kinshasa, which after the 14th century was organized around the African Kongo kingdom, and a second one along the Indian Ocean and the Great Rift Valley. Between these two cultures is an enormous and basically impenetrable (without using the Congo River) jungle to the north and a savannah to the south. Looking at a population density map of Africa, this division remains clear today.

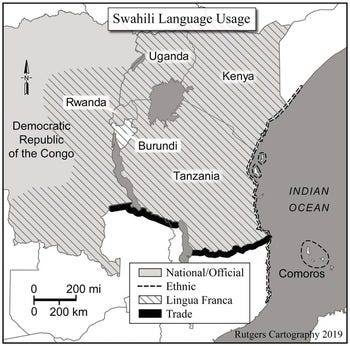

Given their geographic separation, these two groups of people naturally diverged, with the Kingdom of Kongo converting to Catholicism in the 16th century and closely associating itself with the Portuguese, while the eastern nexus was more influenced by Islamic high civilization—although the Great Rift culture’s interaction was primarily through coastal Swahili-speaking people rather than the Arabic world directly. It is worth noting that a major export of both of these societies was slaves for the plantation economies of the Americas and the Middle East. In 2025 these two zones continue to persist and are broadly defined as the regions that use Swahili—which is a heavily Arabized Bantu language.

and regions that speak Kikongo.

It is worth reiterating that although these two cultures do share Bantu agriculturalist roots, they had been effectively separated from each other for thousands of years and had less to do with each other than the descendants of the Indo-Aryans in Iran and those in India.

In the 1880s this changed after the King of the Belgians, Leopold II, launched a scheme to capture the entire drainage basin of the Congo River, ostensibly for humanitarian reasons—centrally the abolition of slave-raiding Muslims. His creation, the Congo Free State, was undeniably a crime against humanity and one of the great tragedies of the 19th century—even if some of its most vocal critics play fast and loose with the data.

Congo (1884–1965)

The period of European colonization of Africa, commonly referred to as the “Scramble for Africa” is in itself extremely fascinating, but what is most relevant for this story is the ease with which Leopold was able to secure a frankly insane amount of territory3. The realization that anyone could just claim an area comparable in size to continental Europe created a sort of feeding frenzy, and in the span of 15 years, Africa was transformed from this to this.

Of course, anyone can claim anything, and to actually own a place, you need to control it. So Leopold went about constructing an elaborate infrastructure program designed both to end Zanzibar slave raiding and to get access to raw ivory and rubber. The colony was the personal property of King Leopold II, which meant he both had huge discretion in his ability to extract wealth and generally wield enormous personal power, but it also meant that he couldn’t rely on the Belgian state finances if his colony ran a deficit. In order to maintain a minimum, “black zero”, while running up huge costs, Leopold and his cronies engaged in massive exploitation of the indigenous population.

This intense demand for cash led to a process I would describe as “scientific plunder,” where 19th-century principles of organizational science were paired with chaotic theft.

The exact scale of its atrocities will never be known, but it got sufficiently out of hand that other 20th-century European states had to pressure the Belgian government to seize control of the colony from Leopold’s direct rule and instead administer it themselves in 1908. By the death of the Free State, huge numbers of Congolese people had died, and the social fabric that had existed prior to Belgian rule had been torn apart.

The Belgians did try to administer their “new” colony along more humanitarian lines—although there was broad continuity. By the Congo’s independence in the 1960s, it was arguably one of the most developed colonies in Black Africa. But you can’t just kill enormous numbers of people without fundamentally destabilizing the psyche of a society.

From a modern perspective, the Congo Free State is truly incomprehensible. Its entire ideological foundation was premised on the moral, biological, and cultural superiority of Whites, which is so alien to modernity, it simply does not compute. But to the people alive in that moment, it was their living experience, as real as the breath you are taking right now.

The Congo Basin had, like much of Black Africa, been subjected to constant slave raiding—in this case by the Kongolese people themselves in the west and Zanzibaris in the east. But the Free State was different: it wasn’t just that the Europeans had conquered and then abused the Africans. No, they had reduced them to the status of untermensch, and that doesn’t wash off easily. It would be like if during the middle of Gilgamesh, an industrial superpower had shown up, destroyed or discredited any semblance of the old society root and stem—from religion to traditional power hierarchies—then ruled tyrannically while insisting on their moral and biological superiority. But more humiliating than anything, it worked. They were more powerful than you; they did know more than you; there was nothing you could do. These scars still run deep in the 3rd world.

But to the Belgian public, who were being fed propaganda about happy “évolués”—literally “evolved ones”—these scars were invisible. “Why would you be offended by my superiority?” This ignorance meant that when riots broke out in 1959, it came as an enormous shock. This was postwar Europe, and there was little interest in really fighting for the Congo, so almost immediately, the Belgian public, who were genuinely under the impression their rule was appreciated by the locals, began the hasty process of getting out. Within less than a year, Belgian colonial rule had disintegrated, and let’s be clear—it was disintegration. Central to this process of disintegration was Patrice Lumumba. Lumumba was archetypical of his generation of African independence fighters. He was an African socialist, clearly extremely bright and educated by the Europeans he would later work to overthrow. Lumumba and many others like him were representative of the contradiction within 19th-century European policies of “uplifting” the natives, since by identifying and raising up the most talented Congolese people, they sowed the seeds of their own destruction.

“This day, sentence of death is pronounced on Shams; judgment of resuscitation, were it but far off, is pronounced on Realities. This day it is declared aloud, as with a Doom-trumpet, that a Lie is unbelievable. Believe that, stand by that, if more there be not; and let what thing or things soever will follow it follow.” – The French Revolution: A History, Carlyle

Like almost all of his contemporary revolutionaries, Lumumba dreamed of creating a pan-African state, at least in his chunk of Africa. Centrally, though, he wanted to transfer control of the economy to the indigenous population. This ran afoul of the extremely powerful European corporations who acted as a central pillar of Belgian rule and who were uninterested in leaving. As happened all over Europe's colonies, even as the Metropole grew tired of the cost of empire, the White diaspora, who had often lived there for centuries, was not interested in leaving.

Thus the whole system just shattered in a sudden explosion of violence in 1960, and whatever delicate progress had been built between 1908 and 1960 came crashing down within only a few months. The Congo crisis is a long story, but the main result of it was the death of Lumumba—along with his canonization as a martyr to many—and the rise of Mobutu Sese Seko as the dictator of the now-rebranded Zaire.

In most of Black Africa, a similar decolonial process occurred, with the main distinction being the point along the chain at which you stopped. First, liberal middle-class Africans began to agitate for more political representation (Senegal). Second, the liberals would be outflanked by an African socialist party that called for independence now, along with nationalization and immediate nativization of most institutions and assets (Tanzania). Finally, either the socialists seized dictatorial power, or more often they were replaced by a military dictatorship whose sole purpose was the extraction of material wealth for an inner clique (Uganda). The Congo, along with states like the Central African Republic, discovered a fifth state: total anarchy. But more on that later.

Rwanda (1884–1996)

Although the modern Congo includes a broad slice of Swahili Bantu culture, the vast majority originally fell under the colonial rule of the Germans. Thus, the kingdom of Rwanda, which long preceded the arrival of the Europeans, fell under the control of Berlin. Both the Germans and then later the Belgians, after WW1, adapted the preexisting structure, and thus Rwanda operated with a relatively high degree of autonomy as a continuous polity throughout the colonial period.

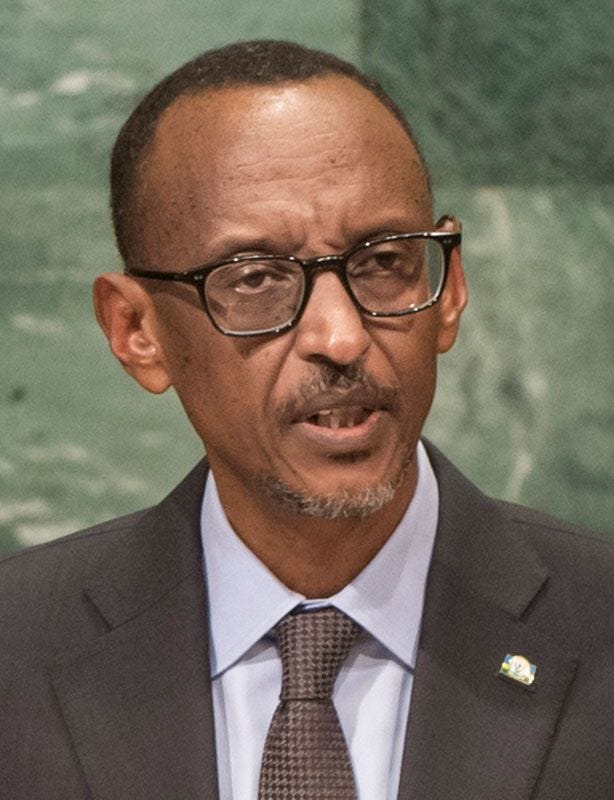

The Rwandan kingdom had a somewhat unique institutional quirk, where basically the entire ruling class of the country were members of a minority ethnic group named the Tutsi. Candid discussion about the exact origins of the Tutsi is difficult to have because of the Rwandan genocide, but the Occam’s razor explanation—based on other human civilizations we do have records for—is that the Tutsi were a foreign ethnic group that conquered Rwanda and then genetically assimilated with the locals while maintaining a distinct phenotype. Because they do have an extremely distinct phenotype. I believe their most famous leaders—Juvénal Habyarimana (Hutu) and Paul Kagame (Tutsi)—each represent their ethnic groups well.

Juvénal Habyarimana

Paul Kagame

Tutsis are taller, more slender, have a less flat nose, and have lighter skin. To steal the language of the 19th century, they were more Caucasoid. This obvious phenotypic fact was like catnip to the European scientific racists of the 19th and 20th centuries, and in a process reminiscent of the formalization of caste in British India, a social system that had already existed was partially codified (or ossified) by colonial administrators. These administrators had little actual access to facts on the ground and a tendency to believe self-interested local elites, facts that combined noxiously.

As Belgian rule gave way to independence, the traditional Tutsi monarchy was replaced by majority Hutu rule, and an increasing spiral of radicalization occurred. Spurred on by the tight association between the former colonial masters and Tutsis in the eyes of the Hutu majority, along with economic and social grievances, the Hutu power groups began to wield increasing power in the country. This violence and radicalization pushed a large number of Tutsis to flee to surrounding countries, primarily Uganda, where they set up a series of refugee camps. The Hutu power government in Rwanda lived in a state of perpetual fear that the Tutsis were going to invade and reinstate the old racial class structure, and they generally fanned these fears in the population through a horrifying campaign of dehumanization. These fears were “confirmed” when, on October 1st, 1990, a Tutsi army (RPF) crossed the Ugandan border and invaded. They were repelled, but their defeat did nothing to calm the tensions in Rwanda; instead, much like the defeat of the first coalition at the Battle of Valmy, which only strengthened the revolutionary hysteria in France, their victory substantially fanned the flames. In 1991 the RPF, now under the command of Paul Kagame, began to wage a guerrilla war with the Hutu-dominated government. While this was happening, Hutu power groups had been secretly (or not so secretly) importing huge numbers of machetes and preparing the population for violence. This continued, with the possibility for a peaceful resolution held together only by the Rwandan president, Juvénal Habyarimana, until April 6th, 1994, when his airplane was shot down.

His death precipitated what we now refer to as the Rwandan genocide, where in the space of 100 days at least 250k, but probably in excess of 500k, Tutsis—along with Twa and moderate Hutus—were murdered, along with a similar number of women raped. This constituted the absolute majority of Tutsis still in Rwanda at that time. I’m not going to discuss the details of this genocide other than to say it is truly one of the most horrifying stories in human history. But the chaos allowed Kagame to restart the civil war and end the killings, although by then the pace was beginning to slow down because of a lack of people left to rape and murder. The Hutus, fearing revenge, fled in huge numbers into the eastern Congo, where many of the architects of the violence lived out the rest of their lives. It is difficult to admit this, but Hutus in Rwanda are about as close to a true story of collective guilt as possible. If you were alive when Kagame entered Kigali, you had participated in the violence—even if only to survive—to a degree that would make any psychologically healthy person sick. Kagame did not pursue a policy of mass revenge, in part because of practicality but also in part because Kagame is a true Carlylian hero, but in 1994 there was no way of knowing this. Once the violence had settled enough, Hutus had fled, and enough Tutsis had returned that in 2025 the demographic balance between Hutus and Tutsis was roughly the same as it was before the genocide.

The Kagame regime was now presented with a new problem. Hundreds of thousands of Hutus now resided in armed refugee camps in the Congo, including huge numbers of génocidaires who were explicitly planning their return. Given that a returning army of refugees was how Kagame had originally seized control of the country, and given the sheer scale of Hutu atrocities, the state needed to act decisively to eliminate the threat.

The Congo at this moment in time was in an absolute wreck. Mobutu Sese Seko, or Mobutu as he is more commonly known, had been running the country since the end of the Congo crisis in the 1960s and was a man of immense avarice. Standards of living were, as much as they could even exist, a third of what they had been under Belgian rule, and the Belgian scientific plunder had been replaced with a just plain regular AK-47 plunder. This plunder had, of course, made Mobutu and his inner circle immensely wealthy.

Zaire had become more and more precarious after the fall of the USSR once US support, he was the man who killed Lumumba, after all, turned into hostility. In brief, Zaire was like every Congolese government, little more than a city-state with the capital of Kinshasa being one of the few places with effective day-to-day centralized control, and the rest of the country existed as little more than a walled garden within whose walls Mobutu could rape and pillage with total impunity.

When, into this decaying state, perhaps a million battle-hardened Hutu extremists emerged, it was a recipe for disaster. Mobutu opted to side with the Hutus, and military units from the Zaire armed forces began to attack Tutsis in the Congo. In return, the local Tutsis began to fight back, which drew in the Rwandan government—which already was keen to intervene—along with their ally Uganda, and the entire Zaire national state collapsed in 6 months. The man who was put in power in Kinshasa, Laurent-Désiré Kabila, proved to be resistant to Rwandan influence, which led to a reinvasion in 1998. This time, however, the government in Kinshasa did not evaporate, and the war turned into a stalemate that drew in almost every neighboring country. By the end of it, the Congo stood in the ruinous state it exists in today.

Unsurprisingly, Rwandan influence over local Tutsis in the eastern Congo never went away, and in 2012 they tried to once again challenge the Kinshasa government. Under international pressure they “disbanded,” and the peace of inarticulate chaos replaced open conflict. Well, Kagame appears to be rolling the dice for a 4th time, and Tutsi militias are once again on the march. I’m not sure even he knows what he wants out of this conflict other than the perennial goals of his regime: protecting Tutsis from Hutu terrorists, defending the eastern Congo from tyranny in Kinshasa, and friction with the essentially non-existent Congolese state over what should and can be done to accomplish these first two goals.

Reflections as an American

America is in a moment of self-reconception right now. Basic assumptions about the role the American Empire is supposed to play in the world are being turned upside down and rethought, sometimes intentionally, sometimes chaotically, but we are metaphysically on the march.

The war in the Congo represents a unique test of this self-examination. The continued formal existence of the Congolese state—the unholy fusion of two distinct African cultures into a single country ruled out of Kinshasa—has never been good for anyone but the central government. For 100 years, America has been a defender of the perpetual sanctity of borders, and this has allowed many regions of the world to prosper. But in Central Africa, it has merely allowed thieves in the capital to use the cover of sovereignty to commit acts of terror on their own population. No rational person can truly believe that North Kivu would be better off under the rule of Félix Tshisekedi than Paul Kagame. One need only cross the border to see how different life could be for those Africans under the rule of a competent government. All across Africa, the locals know in some inarticulate way that they would rather have the anarchy of interstate competition and thus be ruled by the capable than endure Western meddling and the propping up of “democracies”—what does a democracy in the Congo even mean?—who accomplish nothing.

The people in the Congo are just as real as I am. They are real people whose suffering exists and is part of this inescapable experience of sentience. Because of that, I wish for nothing but the best for them. But for their lives to improve, the Congolese state must be strong enough to bring peace. This has not been true since Belgium left in 1960, and it seems the government of Félix is more of the same.

I want to come back to my hierarchy of the state. If the goal is human flourishing, this is impossible without a solid foundation of orderly government and rule of law. As tempting as it is to try and summon the fruit of freedom out of the gnashing teeth of chaos, it is impossible. Because each element builds on each other. Freedom requires laws to adjudicate those areas of reality you can have free agency over and those you cannot4. Laws require order because without ordered processes and consistent application, they are meaningless scraps of paper. Laws are powerless on their own; they do not exist, and nothing will jump out to stop you if you break them. Finally, you definitionally cannot have order in a warzone because war is defined by a suspension of predictable behavior and the anarchy of a death grip.

I do not know what the future will bring for the people of the Congo. Perhaps there is nothing ahead but more war and pandemonium. But if Kagame finally manages to bring peace to North Kivu, I’m not going to pretend to be horrified.

If you've made it to the end of this article, I'd like to suggest you check out my second Substack, "Strong Ideas Held Lightly". For $10/month, I write weekly articles. You can subscribe for free to receive a preview of the paywalled content. If you can’t afford the $10/month and would still like to read my work, DM me.

In fact, it is such a large plate that Substack won’t allow one email to contain it all. If you want to read an untruncated version of this essay, check it out directly on Substack!

“An alarming business, that of governing in the throne of St. Peter by the rule of veracity! By the rule of veracity, the so-called throne of St. Peter was openly declared, above three hundred years, ago, to be a falsity, a huge mistake, a pestilent dead carcass, which this Sun was weary of. More than three hundred years ago, the throne of St. Peter received peremptory judicial notice to quit; authentic order, registered in Heaven's chancery and since legible in the hearts of all brave men, to take itself away,—to begone, and let us have no more to do with it and its delusions and impious deliriums” - Carlyle

The EU is ~1.6M miles^2 miles; the Congo is ~1M miles^2.

From property rights to human rights.

Great piece Peter! “What does support democracy in the Congo even mean?” Is a fantastic question. While I would normally aim to support democratic governments abroad, like in Taiwans case, you pointed out perfectly that you cannot have democracy without rule of law, which in and of itself requires order.

The East Asians Tiger economies are all NOW very successful democratic states, but 40 years they were shepherded by dictatorships. Why should we expect, or even coerce, African countries to be any different?

If, by violating UN recognized boarders in the eastern Congo, Rwanda is able to bring stability, governance, and prosperity to the region - then why shouldn’t we support it? Should imaginary lines on map be valued more than human prosperity?

Very enjoyable and information- dense. Thanks for this.

African countries need to be let alone to find their own angle of repose and form or dissolve as they will. But this will mean millions of deaths through famine and plague and wars fought with spears and machetes. It would also mean immigrant waves in the tens of millions and the frank Africanization of Europe. I doubt future generations would find any of that tolerable and I expect the wealthier and yes supremacist nations (we all know who they are) to actively manage Africa's transition from r-selected hunter-gatherer societies to K-selected civilization. I think the USA with its insane obsession with ideology (the "freedom" in your hierarchy of values) crowds out a lot of creative problem-solving.

Finally, Kagame is a peacemaker and capable ruler but I'd probably look capable with $1B in foreign aid a year too, and I'm not sure countries should put all their eggs in the basket of one nuclear family. Kagame is 67 years old.